“The wickedly entertaining, hunger-inducing, behind-the-scenes story of the revolution in American food that has made exotic ingredients, celebrity chefs, rarefied cooking tools, and destination restaurants familiar aspects of our everyday lives.”

– back cover blurb from…

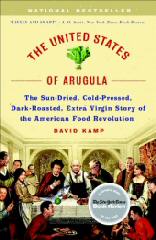

Buenos Aires – …The United States of Arugula, by David Kamp, catchy title, no? Wish I’d have thought of it first. For those of you not in norteamericano foodie circles, this book has been getting a lot of attention since its publication last year in hard cover (paperback edition just came out in July), everything from press reviews to casual offhand remarks, online and off (yes, there is still life offline). First off, let me say that it’s well worth reading, a veritable page-turner of recent food history in the U.S. – I’m not going to say I couldn’t put it down, as I did, several times, because it’s a long book and I had other things to do, but I also read through it, cover to cover, over the course of the last week.

Buenos Aires – …The United States of Arugula, by David Kamp, catchy title, no? Wish I’d have thought of it first. For those of you not in norteamericano foodie circles, this book has been getting a lot of attention since its publication last year in hard cover (paperback edition just came out in July), everything from press reviews to casual offhand remarks, online and off (yes, there is still life offline). First off, let me say that it’s well worth reading, a veritable page-turner of recent food history in the U.S. – I’m not going to say I couldn’t put it down, as I did, several times, because it’s a long book and I had other things to do, but I also read through it, cover to cover, over the course of the last week.

Here’s the good stuff – it’s witty, and I like that. It’s not laugh out loud funny, but it has enough humorous anecdotes, and David Kamp has enough snarky irreverence thrown in to keep a smile on my face through a good portion of the book. It gets into the “history” of the foodie movement pretty well, going very in-depth on a few stories, James Beard, Julia Child, and Alice Waters in particular are covered at length and breadth, and resurface throughout the book. It’s well organized, starting with at least a mention of the late 18th century and moving on up to what was present day when it was written. I knew a good number of the stories already, but not in so much detail, and, of course, I’m in the business, so a lot of the people in the book are people who I know either casually or well. And hey, there are a few stories that I could… well, never mind.

On the other hand, and you knew there’d be one… while he acknowledges that food didn’t spring miraculously into existence with the arrival of James Beard on the scene, quoting Barbara Kafka, “It’s like there was no food in this fucking city, or this country, until this miraculous apparition came along! Or there was no cooking at home until Julia.” But then, he promptly manages to cover the entire period from the 1790s until the 1930s in a matter of a few pages, and even in those keeps returning to the latter part of the 20th century, and then covers the period from the 1930s until the early 60s in less than a dozen pages, most of which are focused on one restaurateur, Henri Soulé. But, in a sense, that’s in keeping with the style of the book – its focus is on some very select individuals and their stories, with others coming into play more as peripherals – not that he doesn’t give those extras some page time, but I was left feeling like they were propping up his main characters – for the most part, the three folk listed above, whom, after reading the book, did I not know better, could have pretty much done it by themselves, with a few food writers thrown in for good measure.

The book is, not surprisingly, coastal-centric… if one can be coastal and centric at the same time – focusing mostly on the food scene in New York, the San Francisco Bay Area, and a bit in Los Angeles. While there’s no question that a huge amount of the modern food movement, and in particular the public figures in it, come from those areas, I think he gives short shrift to the rest of the country. Someone like Norman Van Aiken, the godfather of “Florida cuisine” doesn’t even make an appearance in the book. Ming Tsai (who ought to fit his celebrity criteria) is nowhere to be seen. His ethnic influences seem limited to French, a nod to Italian (Mario Batali apparently invented Italian food in the U.S. with the help of ingredients from Dean & DeLuca), Mexican (Rick Bayless and a bit of Bobby Flay doing the same for south of the border cuisine, with a very brief nod to Mark Miller and Diane Kennedy, whom, we gather, did lots of research but not much else), and a bit of Japanese, in particular sushi, and in particular the famed Masa and Nobu. There is, in essence, no mention of other influences – China, India, Southeast Asia, the entire rest of Latin America, the Middle East, the rest of Europe, Africa, Austraila (admittedly the latter two have yet to have any major impact on cuisine in the U.S.) – the influence of Chinese cuisine is covered in three widely separated paragraphs, Craig Claiborne meeting the authors of a Chinese cookbook, a mention of Michael Field’s review of a different Chinese cookbook, and Wolfgang Puck bringing Chinese influence (apparently for the first time on our shores) into his restaurant Chinois. The only mention I recall of all of Latin America outside of Mexico is a brief cameo by Felipe Rojas-Lombardi, from Peru.

But the biggest “missing” for me were the people, the “ordinary” people. I know that this book is focused on the celebrities – and let’s face it, that’s really what it is, a mixed celebrity bio, which for the most part in this tome means someone who has appeared regularly on television – and anyone who isn’t or wasn’t a celebrity is simply either ignored or discounted – does he really need to remind us, every time he mentions something good that Craig Claiborne did, that in his later years he “declined” into alcoholism, and how many times do we need to hear that James Beard was fat? Or repeatedly pointing out that they were gay, which, if it was somehow worked into their influence on the food scene might have been relevant past the first mention. Or that nobody really likes, or ever liked, Alice Waters…? The people missing, however, are more than just the rest of the professional food world in the U.S., they are the people who were eating all this food. The tenor of the book comes across that 99.99999% of the populace were pretty much dragged, kicking and screaming, forced at gunpoint, to try anything new. There seems to be no awareness, and certainly no acknowledgement, that what made it possible for these chefs and food writers and food growers/raisers to do what they did is that We, the People, were actually a prime part of the equation – from immigrants hungering for foods of their homelands, to GIs who’d been overseas and came back with stories to tell of things they’d eaten, to the world simply “becoming a smaller place” with international travel, global media and in recent years, phenomena like, for example, hey, food communities on the internet, where we were actually actively seeking out the new, the exotic, the different – the social, cultural, political world that influenced the culinary or gastronomic environment into which these people could flourish and become the celebrities that they have.